[ BLAST FROM THE PAST ]

Advertising without a net in Kyrgyzstan

Originally published in Marketing Magazine, October 21, 1996

The voice on the phone had assured me that this ancient pit-stop on the fabled Silk Route had all the charms of a Mediterranean resort — lushly treed boulevards, exotic cafés, all set against a spectacular mountain backdrop. Casually left unmentioned was the collapsed infrastructure, cruel climate and Third World poverty. But, hey, who’s complaining? The assignment did turn out to be the adventure of a lifetime.

Six years ago, escaping from a recession-walloped Canada, I grabbed at the opportunity to join the creative department of Young & Rubicam’s newly opened Moscow office. Years spent with the agency in Montreal had not prepared me for those heady times. It was uncharted territory, what with the sudden disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Although we took care of the usual roster of multinational clients, the bulk of the agency business was servicing lucrative Western government contracts, millions of foreign-aid dollars poured into projects to nudge the Russians along in their move to a market economy. The star account was promoting privatization, a key policy of the Yeltsin government, through a massive advertising blitz. I art directed the campaign for a stretch.

After wrapping up the project in 1993, I was dropped the next year into this remote, former Soviet province to help the newly independent government explain to its citizenry a controversial privatization plan. The state was redistributing its wealth (what remained of it) into private hands and wanted as many people to benefit as possible. USAID, the American foreign-aid agency, was footing the bill. The mission was to persuade a clear majority of the Kyrgyz populace to participate in the giveaway by year’s end.

A good old-fashioned ad campaign was expected to do the trick where all else had failed in a mostly rural society of nomadic sheepherders. It would be the country’s first advertising. A skeptical population had already watched a previous privatization scheme flop miserably.

As creative director of the pompously named Public Information and Education Campaign, my first task was to pull together a viable work plan within 24 hours. Nothing like mayhem to get the creative juices flowing.

To rescue the operation, a logo was proferred as immediate proof of our competence and grandly publicized American know-how. The symbol, a stylized sun lifted from the country’s new flag, would instantly provide a visual identity for the campaign. It would associate privatization with the popular nationalist movement. It would also be red, since I could be sure there’d be red ink in plentiful supply at abandoned communist printshops.

I was determined to impose an umbrella creative strategy on the client’s disparate list of demands. The pioneering Russian campaign had, alas, unfolded as a chaotic succession of ad hoc messages promoting the political agendas of infighting Kremlin bureaucrats. Ultimately, that campaign rested on the power of its memorable logo: a simple, Cyrillic rendition of the word Privatizatsia (Privatization) with the za (indicating the affirmative — yes!) underlined.

This time around we would create a model campaign. Privatization would be sold to Kyrgyz ‘consumers’ the same way as toothpaste elsewhere.

Images of beaming children, symbolizing hope and a new start, would be central. A cliché perhaps, but it might humanize privatization, an abstract and complicated term. Several campaign theme-lines were tested in quickly organized focus groups. My favourite, Invest in Yourself, simply didn’t translate into Kyrgyz — the individual and finance apparently being foreign concepts. The crowd-pleaser turned out to be Invest in Your Future, a logical complement to visuals of grinning descendants.

What would normally be the most terrifying aspect of producing an ad campaign — selling it to the client — turned out to be child’s play. The Kyrgyz minister eagerly signed his approval. Perhaps he was impressed by our slick presentation. Perhaps he was simply indifferent.

And so, we set out to alter the thinking of an entire country. We had the mandate to mount a full-blown, Western-style ad campaign, but none of the support services — typographers, commercial production companies, colour separation houses, or pizza delivery.

Panic set in.

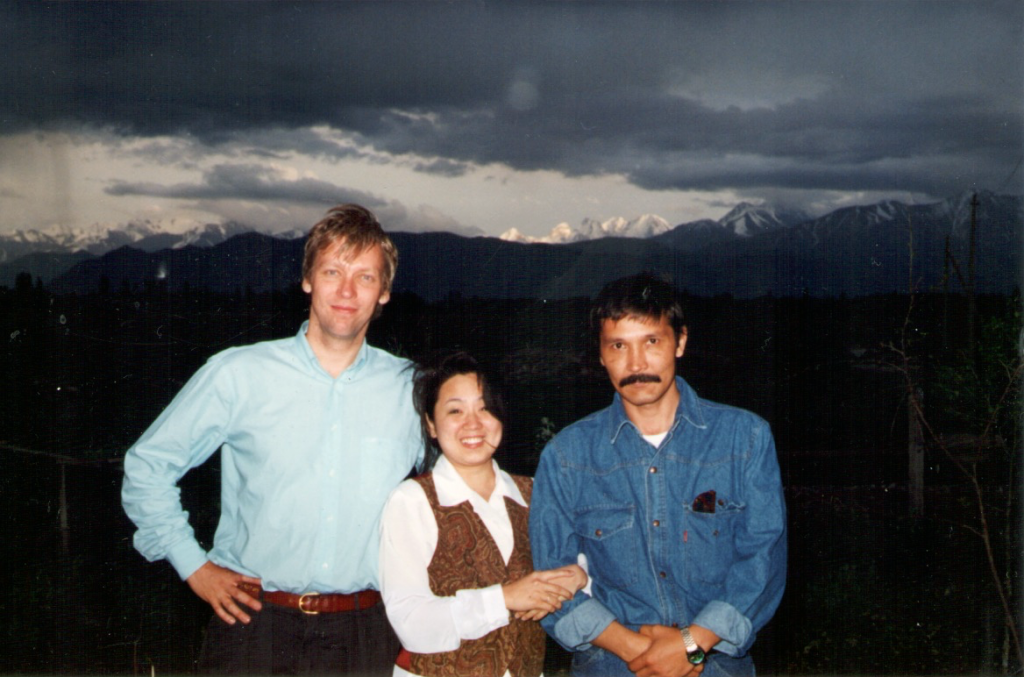

Luckily, I discovered an English-speaking Kyrgyz partner, Nourghiz, who became my trusted guide through the treacherous mountains that lay ahead. I did not speak the language or have an understanding of eastern ways. Nourghiz would bluntly tell me what worked and what didn’t.

Laptop at the ready, I churned out the first ads. Nourghiz adapted them into the Kyrgyz and Russian languages. The launch TV commercial, a 60-second spot, was pure image: emotive faces superimposed over a close-up sun rising over the Kyrgyz Alps. The only words were the signature ‘Privatization. Invest in Your Future.’ Evocative imagery would capture attention and direct the viewer to the hard sell in print media.

Each information-laden newspaper ad, in turn, was branded with a portrait captioned with child’s name and the legend ‘future owner.’ The copy was written in a folksy tone, a refreshing departure from Big Brother’s usual lumbering formality.

At first, the campaign met various forms of resistance. Newspaper ads were mutilated by editors who didn’t understand the concept of a paid advertisement. I would open the morning paper to find headline and copy rewritten to reflect the particular political views of the paper’s editorial board.

Since the state-unsubsidized publishers were desperate for dollars, they soon came to recognize the sanctity of the paid advertisement and its separation from editorial. The papers continued to lambaste the program in their own space.

As the campaign developed, it was constantly finessed, always responsive to concerns of the ordinary citizen. No one would be neglected. Borrowing from Lenin’s arsenal, a traveling roadshow of variety entertainers was dispatched to isolated mountain hamlets to spread the word.

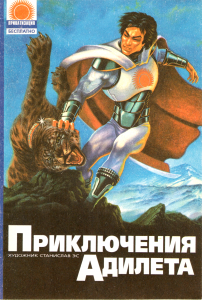

Teens could not be ignored as they comprised a sizable chunk of the population. To engage them (as well as semi-literate adults), we published an educational comic book with a Superman-type character loosely based on a Kyrgyz folk-hero. Our hero would fight evil and corruption (SLAM! KABOOM!) while explaining basic privatization facts on the side.

Then scandal erupted. The privatization minister himself was suddenly sacked by the president, indicted on corruption charges. That day, by coincidence, a full-page ad was scheduled to run, launching the comic book and its hero. ‘Introducing the Privatization Agency’s Newest Employee’ ran the headline, with copy about how no one was shielded from the vigilant gaze of the local superman. Cheeky as this was, the Kyrgyz had the moxie to run the ad, thus nicely quashing a PR disaster.

The campaign’s efficacy was tracked by the usual tools of research. I was surprised at how instrumental focus groups had been in guiding the creative. Grassroots feedback kept our material focused, honest.

Disgruntled fortysomethings repeatedly told us that this privatization thing might not dramatically improve their own lives, but their children would inevitably reap rewards. Whatever they thought of the politicians, politically they believed there was no other way to go. They had read our ads.

One short year later, an independently commissioned survey confirmed that a remarkable 76% of the population had indeed taken advantage of the government’s property redistribution scheme. The dirty P word had registered minor (but respectable given its notoriety) improvement in public opinion. Mission accomplished.

For me personally, it was an intensely gratifying year. A chance to witness history, to watch a society transform, to learn about another country. There was pain and agony, but also small achievements, progress. Plus I got to do some great ads.

Before long, the country’s new private enterprises — shops, banks, airlines — began running their own advertising, some of it not bad at all. •

—Uno Ramat

Watch the TV commercials here.

Watch the Caravan Show here.